“We’d come all the way through the mine-filled Channel and now were sitting below the high yellow-green cliffs of Normandy surrounded by more ships than I had ever seen in my life or even knew existed. Thousands upon thousands of them made up the armada, massive destroyers and transport vessels and battleships. Small snub-nosed boats and cement barges and Ducks carried troops to the beaches, which were alive with pure chaos. Once they made the beach, there were two hundred yards or more of open ground to survive and then the cliffs. Overhead, the sky was a thick gray veil strung through with thousands of planes.”

“We’d come all the way through the mine-filled Channel and now were sitting below the high yellow-green cliffs of Normandy surrounded by more ships than I had ever seen in my life or even knew existed. Thousands upon thousands of them made up the armada, massive destroyers and transport vessels and battleships. Small snub-nosed boats and cement barges and Ducks carried troops to the beaches, which were alive with pure chaos. Once they made the beach, there were two hundred yards or more of open ground to survive and then the cliffs. Overhead, the sky was a thick gray veil strung through with thousands of planes.”

There had never been anything like it, nor would there ever be.” – Love and Ruin, by Paula McLain

I didn’t know that Martha Gellhorn, war correspondent and Ernest Hemingway’s third wife, was the only reporter with the Allied troops when they landed at Normandy on D-Day, and the only woman among 160,000 soldiers. At a time when female journalists were not permitted on the battlefield, Martha stowed away on a hospital ship the night before the landing. Ernest Hemingway and other male reporters tried their utmost to gain access to the battlefield that day; where they failed, Gellhorn succeeded magnificently. Her story has been beautifully re-created by Paula McLain in Love and Ruin.

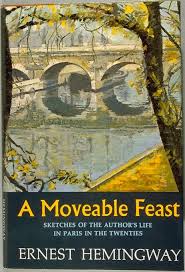

I’m not typically a fan of fictionalized versions of real people’s lives, but I trust McLain because I’ve enjoyed her other novels: Circling the Sun, about Beryl Markham, and The Paris Wife, which depicts Hemingway’s relationship with his first wife, Hadley.

I’d assumed that by the time he met his third wife, Ernest Hemingway was well on his way to burning out, but that is not the case. Hemingway was at his peak and the most famous living writer in the world when he and Martha Gellhorn began a passionate love affair while he was married to his second wife, Pauline.

Martha Gellhorn was a ravishing beauty; she and Hemingway had a powerful mutual attraction. Martha had just published her first novel, and Hemingway mentored Martha to a degree unusual for male writers of his day. He encouraged her to dodge bullets, bombs, and mines with him as they covered the Spanish Civil War, Martha’s first immersion as a war correspondent. Hemingway has said that Gellhorn inspired him to write For Whom the Bell Tolls, which he dedicated to her. For a handful of years, Hemingway and Gellhorn enjoyed an extraordinary literary collaboration.

“….I loaded into a cement ambulance barge with a handful of doctors and medics, crashing through the surf around floating mines lit up by a flashing strobe. Soon I would know we’d landed on the American sector of Omaha Beach, but for the moment there was only horror and chaos. We bumped through severed limbs and the bloated forms of the drowned. Artillery fire shattered the air in every directions. Planes roared over us, so close my skull vibrated, but there wasn’t even time to wonder whose side they were on.”

I found Paula McLain’s depiction of Hemingway in Love and Ruin to be somewhat thin. For me, her rendering of Hemingway and his first wife, Hadley, in The Paris Wife was far more emotionally compelling than that of Hemingway and Gellhorn, but that didn’t take away from my enjoyment of Love and Ruin.

I think what interested Paula McLain (and me, too) is Martha’s larger-than-life risk-taking, how it matched Hemingway’s, and how their love for each other fueled their work. Ultimately, their relationship didn’t – and probably couldn’t – last, given Martha’s independent spirit and Hemingway’s sexism – he was a male of his time. Hemingway betrayed Martha terribly, in more ways than one, when she would not stay home by his side and have a child.

“Near the beach, we flung ourselves out into the icy water and waded to shore. The surf came to my waist and tugged at my clothes. I stumbled, feeling chilled to my core, but I couldn’t be dragged down. I had to hold up my end of the stretcher and stay between the white-taped lines that marked the places that had been cleared of mines.

We picked up everyone, anyone, even Germans, and assembled them all on the beach for triage. They were young and scared and cold and hurt, and it didn’t really matter how they’d been wounded, or who they were before this precise moment of need. Every last one of them made me feel gutted, and there were hours of this. Blood-soaked bandages, flares sailing like red silk over the beach with a pop, tanks, and bodies. Men and more men. Men with boys’ faces. Boys spilling their lives into the tide….

It was the strangest and longest night of my life. Later I would learn that there were a hundred thousand men on that beach and only one woman, me. I was also the first journalist, male or female, to make it there and report back.”

After Hemingway, Martha Gellhorn continued to have a full, rich life. She wrote prolifically into her eighties, publishing novels, nonfiction, essays, and plays, and covered every major war during the second half of the twentieth century, including Viet Nam. Gellhorn, photojournalist Dickie Chapelle, and a handful of other brave women blazed a trail for the many more great female war correspondents to come.

Given that journalists are being called “enemies of the American people,” and many reporters are deeply concerned about the threats of violence they receive daily, I think it’s timely and fortunate that Paula McLain has celebrated Martha Gellhorn in her latest novel.

“The Women Who Covered Viet Nam” is an excellent article written by war correspondent Elizabeth Becker, a good, short read if you’d like to know more about women reporters of that era. For a riveting story about a contemporary war correspondent who lost her life, read “Marie Colvin’s Private War” in Vanity Fair. Town & Country recently featured an article about Martha Gellhorn written by Paula McLain, with great historical photos. Goodreads has a list of memoirs by women journalists.

Here, Paula McLain talks about Love and Ruin at Mentor Public Library, a suburb of Cleveland (my hometown!) where McLain currently lives:

Here, she talks about poetry and inspiration:

Have you read Love and Ruin, or any of McLain’s other novels? If so, what did you think? Let us know in the comments.