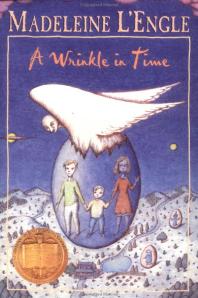

I remember the book, which I think of as my Hunger Games book, and I remember the reading of it. Where I was (in my bedroom, my favorite place to read), how old I was (ten), and how I started reading as soon as I got home from school and didn’t stop until I reached the end sometime after dark.

In A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle, Meg Murry wore glasses like me (she had a habit of pushing them up on her nose, just like me) and braces, (me too) and her hair never looked quite right (me too, again). She was a social misfit in danger of being held back a grade in school. I could slip easily into Meg’s skin; even though I had plenty of friends and good grades, I felt I could lose my tenuous social standing in a flash if anyone found out about my strange mother who, around that time, had succumbed to mental illness.

In A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle, Meg Murry wore glasses like me (she had a habit of pushing them up on her nose, just like me) and braces, (me too) and her hair never looked quite right (me too, again). She was a social misfit in danger of being held back a grade in school. I could slip easily into Meg’s skin; even though I had plenty of friends and good grades, I felt I could lose my tenuous social standing in a flash if anyone found out about my strange mother who, around that time, had succumbed to mental illness.

It was as if the book had been written just for me. As if, somehow, L’Engle had looked into my soul and put all of its good parts and bad parts right there on the page. I felt recognized for what I was. Understood. Authenticated.

Meg’s family was like no other family I’d ever heard of. Her mother, Katherine Murry, was the mother I wanted: a beautiful, brilliant scientist who ran experiments in the kitchen pantry. There weren’t many scientist moms in 1965 Cleveland, Ohio, and Mrs. Murry’s brand of strangeness was the kind I could live with. (She won the Nobel Prize in a later book by L’Engle, but always had home-made cookies waiting for Meg and her younger, genius brother, Charles Wallace, when they came home from school.) Meg’s Princeton educated father worked at Cape Canaveral and had been away for a long time on a secret mission. The gossip was that he’d abandoned his family.

Meg’s friend, Calvin O’Keefe, was a revelation to me, too. He made it clear you could be from an unhappy family and still be your own strong, separate self. He was kind, popular in school, and a talented basketball player (yes, way too good to be believable) even though his mother had missing teeth, wispy, gray hair, and paddled her children with wooden spoons.

Meg, Charles Wallace, and Calvin are swept away to another dimension to search for Meg’s father and fight a great evil. I was swept away with them. This was new territory for me. I didn’t typically read fantasy or science fiction and I’d never encountered such odd, mesmerizing characters. L’Engle based the sci-fi elements of her story on Einstein’s theory of relativity, and I had always been fascinated by outer space and its mysteries. Yet, for all of its science, A Wrinkle in Time is infused with spirituality, too, and though I couldn’t have verbalized it back then, that fusion of science and spirituality rang true for me. And while L’Engle invoked Christian themes I could relate to, she gave equal time to the Buddha, Gandhi, and the great artists. This was a viewpoint I hadn’t considered before.

A Wrinkle in Time, for me, was an escape from unhappiness, a preview, in Katherine Murry, of what a strong woman could be, and a glimpse of a different, more complex world than my own familiar one.

Many years later, I met Madeleine L’Engle when she spoke at the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine in New York City, where she was the librarian and writer in residence. We shared a neighborhood, those blocks clustered around the massive Episcopal cathedral. As she spoke about her life and her beliefs, I recognized the themes I’d encountered in her fiction: a passionate spirituality inseparable from a reverence and respect for the laws and mysteries of the cosmos.

When I was doing research for this post, I discovered that this year is the 50th anniversary of A Wrinkle in Time. When it was published half a century ago, it won the Newbery Medal. Yet, because it combines fantasy with an inclusive spirituality, (rather than an exclusively Christian one) A Wrinkle in Time is often on banned book lists in schools across the country.

*****************

Did you have a Hunger Games book when you were growing up? If so, tell us in the comments below.

New and Selected Poems, by Mary Oliver, published in 1992, includes poems from 1963 – 1991.

New and Selected Poems, by Mary Oliver, published in 1992, includes poems from 1963 – 1991.