I first published this post in May, 2012, when we were staying in a remote cabin near the town of Index in Washington State’s Cascade Mountains. I was also reading the novella, Train Dreams, by Denis Johnson. I’m reposting it now because the gorgeous movie adaptation has just been released. (It is currently in theaters and on Netflix.)

Train Dreams is a beautifully filmed, meditative story about an early 20th century Idaho logger who travels to Washington and environs to work on crews that take down the largest trees in the forest. I promise you, the movie will sweep you away, completely and utterly, to another time and place. New York Magazine calls Train Dreams a staggering work of art, and they are right. The translation from book to film is flawless, and those of us who are avid readers know how special it is when the essence of a beloved book comes to life on the screen.

Here is my original post:

Just steps from our front door, the peaks of Mount Index are illuminated in great detail by the last rays of sun.

It’s spring and we’re in Washington’s Cascade Mountains. This is wild, intimidating territory. Rivers and creeks rage as snow melts in the mountains. Along the highway, as we made our way here, we passed by dozens of cascades of snowmelt tumbling down steep walls of rock on either side.

Our vacation cabin is perched on the banks of the Skykomish River. It was raining our first night here, and the rain, together with the rushing river, created quite a din. The mountaintop had been hidden by fog.

We built a fire in the wood burning stove, which took the chill out of the air and made everything cozier. Later in the evening, a dull roll of thunder swelling to a roar overpowered the sounds of downpour and river flow outside our picture window. My first, nervous thought was “flash flood,” but when the high-pitched whine of metal-on-metal joined the mix, we realized the sound was a train.

We are in high train country. The legend of the Great Northern Railroad is very much alive here, though nowadays the trains that run are mostly on the Burlington Northern Santa Fe line. Twice now, while having lunch at the Cascadia Hotel Cafe in Skykomish, we’ve watched trains pass through, heading east from the port of Seattle with container cars from China, Germany, and Scandinavia.

Several times a day and into the night we hear the trains.

In a kind of parallel journey to my vacation, I’m reading Train Dreams, a novel by Denis Johnson about a logger and laborer who worked for the Pacific Northwest train companies of the early twentieth century.

The Pacific Northwest is surreal and dangerous in Train Dreams, as much a character as Johnson’s protagonist, Robert Grainier.

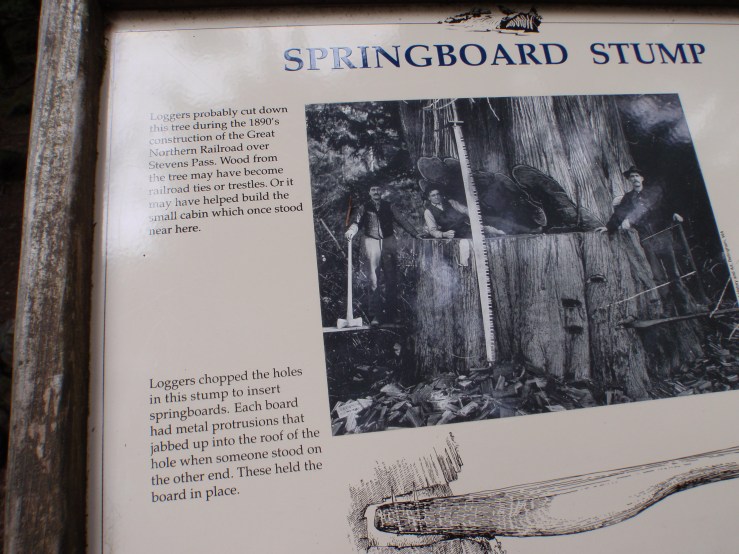

I thought about the life and times of Grainier when we hiked the Iron Goat Trail the other day, along the now abandoned Great Northern Railway bed. On plaques along the way, old photographs depicted loggers like Grainier taking down giant cedar and fir trees.

Grainier grew “hungry to be around….massive undertakings, where swarms of men did away with portions of the forest and assembled structures as big as anything going, knitting massive wooden trestles in the air of impassable chasms, always bigger, longer, deeper.”

Yet Grainier also saw the great mountains and forests defeat the ambitious plans of mere humans. The land defeated him, too, in a very personal way, but he learned acceptance and, finally, a kind of reverence for the terrible beauty of the place he called home.

The Iron Goat was the last spur of the Great Northern Railway, crossing the Cascades at the treacherous Stevens Pass. I found Stevens Pass stunning the first time we drove through, going east at sunny noon. But on the late afternoon return trip, when it was foggy with rain turning to sleet, I could hardly stand the vertigo as we tried to avoid skidding on the slick highway.

Disaster Viewpoint on the Iron Goat Trail marks the spot where, in 1910, an avalanche swept two snowbound passenger trains into the Tye River below, killing nearly 100 people.

To alleviate the dangers of avalanches, the railroad companies eventually built snowsheds, huge retaining walls to protect trains from tumbling snow. My husband and I walked alongside an old snowshed on our hike.

We knew our hike would be cut short because a sign at the trailhead indicated an avalanche had made the trail impassable a half mile in.

Sure enough, just a few feet from where the snowshed ended, we could go no further, thanks to a wall of hard-packed, dirt-encrusted snow.

“All his life Robert Grainier would remember vividly the burned valley at sundown, the most dreamlike business he’d ever witnessed waking—the brilliant pastels of the last light overhead, some clouds high and white, catching daylight from beyond the valley, others ribbed and gray and pink, the lowest of them rubbing the peaks of Bussard and Queen mountains; and beneath this wondrous sky the black valley, utterly still, the train moving through it making a great noise but unable to wake this dead world.” – Denis Johnson, Train Dreams

Train Dreams, Denis Johnson, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York, 2011.

“In the annals of literary ‘fallen women,’ Kristin Lavransdatter, the twentieth-century/fourteenth-century literary figure, occupies a curious and fascinating place. After they fell, a number of Kristin’s nineteenth-century counterparts were whisked offstage, often to meet a premature end. In the latter part of the twentieth century, many of Kristin’s successors were sexual adventuresses whose exploits were pure and liberated triumphs. Writing in the first quarter of the twentieth century, Undset chose a middle path for her heroine. Kristin never doubts that she has covertly sinned, and the pain of her deceptions remains a lifelong affliction. Even so, her unshakable guilt in no way paralyzes her and she carries on with her life. Throughout the trilogy, Kristin is an indomitable presence in every role she undertakes….”

“In the annals of literary ‘fallen women,’ Kristin Lavransdatter, the twentieth-century/fourteenth-century literary figure, occupies a curious and fascinating place. After they fell, a number of Kristin’s nineteenth-century counterparts were whisked offstage, often to meet a premature end. In the latter part of the twentieth century, many of Kristin’s successors were sexual adventuresses whose exploits were pure and liberated triumphs. Writing in the first quarter of the twentieth century, Undset chose a middle path for her heroine. Kristin never doubts that she has covertly sinned, and the pain of her deceptions remains a lifelong affliction. Even so, her unshakable guilt in no way paralyzes her and she carries on with her life. Throughout the trilogy, Kristin is an indomitable presence in every role she undertakes….”

Kingsolver sometimes uses her characters as mouthpieces for her themes and political beliefs, and she does this whole-heartedly in Unsheltered. The dialogue is preachy and tiresome, especially between the modern-day out-of-work journalist and her professor husband. Granted, the two are intellectuals, but I found their conversations (even in bed!) heavy-handed and unbelievable.

Kingsolver sometimes uses her characters as mouthpieces for her themes and political beliefs, and she does this whole-heartedly in Unsheltered. The dialogue is preachy and tiresome, especially between the modern-day out-of-work journalist and her professor husband. Granted, the two are intellectuals, but I found their conversations (even in bed!) heavy-handed and unbelievable.

“We curse the U.S. government, we curse the Army, we curse the savagery of mankind, white and Indian alike. We curse God in his heaven. Do not underestimate the power of a mother’s vengeance.”

“We curse the U.S. government, we curse the Army, we curse the savagery of mankind, white and Indian alike. We curse God in his heaven. Do not underestimate the power of a mother’s vengeance.”  “We’d come all the way through the mine-filled Channel and now were sitting below the high yellow-green cliffs of Normandy surrounded by more ships than I had ever seen in my life or even knew existed. Thousands upon thousands of them made up the armada, massive destroyers and transport vessels and battleships. Small snub-nosed boats and cement barges and Ducks carried troops to the beaches, which were alive with pure chaos. Once they made the beach, there were two hundred yards or more of open ground to survive and then the cliffs. Overhead, the sky was a thick gray veil strung through with thousands of planes.”

“We’d come all the way through the mine-filled Channel and now were sitting below the high yellow-green cliffs of Normandy surrounded by more ships than I had ever seen in my life or even knew existed. Thousands upon thousands of them made up the armada, massive destroyers and transport vessels and battleships. Small snub-nosed boats and cement barges and Ducks carried troops to the beaches, which were alive with pure chaos. Once they made the beach, there were two hundred yards or more of open ground to survive and then the cliffs. Overhead, the sky was a thick gray veil strung through with thousands of planes.”