“Where do I come from?” – Jung and the Ancestors: Beyond Biography, Mending the Ancestral Web by Sandra Easter

“What is being asked from us in the present in relationship to the past and unfolding future?” – Sandra Easter in Jung, etc…

Morfar

Things were not going so well.

As I boarded the plane in Madrid for the last leg of our flight to Sweden, the handle on my brand new luggage broke. Inside, the bins on both sides of the aisle over my seat were filled with first aid equipment. The nearby bins were full, too. When I asked the steward where I should put my luggage, he snapped, “Do you want me to make the plane bigger? I can’t make the plane bigger just for you!”

What happened next, Carl Jung might call a synchronicity.

I left my suitcase in the aisle and squeezed into my window seat in the last row of the plane, next to a beautiful young Swedish woman, Amelie. As if the universe were making sure I paid attention, Amelie’s face bore a striking resemblance to my former college roommate and close friend, Kathy, who has Norwegian ancestry. Except that Amelie’s hair was ice blonde instead of dark, and her eyes, instead of brown, were brilliant blue.

While another, calmer, steward found a place for my suitcase, I talked with Amelie, who is a physician and a mom. I told her I was visiting Sweden for the first time, in part to research my family history. Mormor, my maternal grandmother, was from near Falkenberg on the Swedish west coast; Morfar, my grandfather, had been born in the rural, inland town of Fritsla. After sightseeing with a friend in Stockholm, I’d be heading to Falkenberg and Fritsla with my son.

“I grew up in Fritsla,” Amelie said. “In fact, my father has been researching the history of our family and the town.”

We couldn’t believe the coincidence.

I told Amelie that I knew very little about my grandfather, who had been an orphan. Apparently, he’d been raised by an aunt and uncle after he lost a parent and a sibling in a flu epidemic. My Swedish grandmother, Mormor, had often corresponded with family back in Sweden but, as far as I knew, Morfar hadn’t communicated with anyone in Sweden after he came to America.

By the time I knew him, Morfar was a solitary man who rarely spoke. He’d sit in his living room chair and gaze out the window for hours, then disappear when no one was looking, which upset Mormor, who would then go and fetch him from the corner bar.

I had always wanted to learn more about my Swedish roots, especially because growing up I’d felt distant from both of my parents’ extended families. My mother’s schizophrenia made her isolated and uncommunicative. She didn’t go to Sweden when my aunts traveled there in the early 1990s to meet their aunts and uncles and cousins, nor did she enjoy having visitors in our home. When relatives came to see us, they didn’t linger; the relationships my brothers and I had with them were markedly curtailed. These restrictions frayed our kinship, diminished well-being, and made keener my lifelong desire to connect with our larger family.

Trauma is a risk factor for serious mental illnesses. It’s theorized that the effects of trauma might be passed down through generations via genes that become “tagged,” or marked, in some way. So my mother’s troubled history made me extra curious to learn more about my grandfather’s life, since I knew his childhood had been difficult.

Even if the gene tagging theory isn’t correct, I believe the trauma and fallout are passed down in other ways. The further I got on my Swedish odyssey, the more it struck me how little many of us know about our ancestors, how missing they are from our lives, and how incomplete that makes us. What a loss.

***

“I had the feeling that I was a historical fragment, an excerpt for which the preceding and succeeding text was missing. My life seemed to have been snipped out of a long chain of events, and many questions remained unanswered.” – Carl Jung, as quoted in Jung, etc by Sandra Easter

***

Talking with Amelie kept my mind off of the turbulence, the swirling dark clouds, and the sleet outside the airplane window. She told me about her work at a medical clinic in Stockholm. She’s a reader, too, and we talked about Swedish and American literature. She showed me pictures of her beautiful children, and I showed her old family photos on my smartphone. Amelie offered to see if her father could find out anything about my grandfather and his family.

As the plane approached Stockholm, it broke through the thick layers of gray-white clouds. I saw Sweden for the first time: lush, rolling hills; sparkling lakes the color of Amelie’s eyes; dense forests; and land cultivated in orderly rows, dotted with red farmhouses and outbuildings.

During my week in Stockholm, I received an amazing surprise via email from Amelie and her father: a detailed, multi-page history of my grandfather and his family, complete with photos and documentation, culled from Swedish sources and translated into English.

This information would prove invaluable to understanding my grandfather’s childhood, and provide us with an itinerary of locations to visit in Fritsla. But first, we stopped in Älekulla to meet my cousin Jan and to see the land where my grandfather’s grandfather had lived.

“….Originating in what Jung refers to as the ‘mighty deposit of ancestral experience,’ each individual life originates in and is woven into this infinite ancestral story, this ‘original web of life.’ The fine thread of our fate, woven into ‘all the events of time,’ is connected to the lives of our ancestors and our descendants. Each of us is a unique response to all that has come before and all that will come after.” – Jung,etc.

I’m sure that life wasn’t easy for my grandfather’s farming ancestors in Älekulla. But I sensed they were bolstered by a strong faith, a deep connection to family, the land and their community, and a shared history going back generations.

As I would learn in part from Amelie and her father’s report, these blessings were not nearly as present in the lives of my great grandfather and my grandfather. More about that in my next post.

My son and I discovered that researching our roots is also about the journey itself, and the extraordinary people you meet along the way. Many thanks to Amelie Sandin, Pär Sandin, Jan Andersson, Jan-Åke Stensson, Irene Svensson, and Gunvor, who restored to my son and me many of the beautiful fragments of our family history. I hope we can return one day to learn more and to see these kind, generous people once again.

“Each one of us as a ‘historical fragment’ within a longer story, comes into this world with a particular ‘pattern’ that is, according to Jung, a response and answer to what is unresolved, unredeemed, and unanswered. The pattern of our particular life, our genius and gifts, become evident and are developed as we listen and respond to the ‘lament of the dead’ with love. Every person, every gift is an important part of the integrity and well-being of the interconnected web of kinship. Engaging in a more conscious dialogue with the ancestors, each of us can more consciously and fully live the life that is ours alone to live. Doing so contributes to the well-being of all our kin. I would suggest that in addition to our lives being a response to what is waiting for resolution, redemption, or an answer, each of our lives is also in service to our descendants.” – Susan Easter in Jung, etc. (Boldface is mine.)

********

During the months and weeks I prepared for my trip to Sweden, 16-year-old Swedish activist Greta Thunberg made great strides drawing attention to climate issues. In March, she was nominated for the 2019 Nobel peace prize. Her work speaks to those who believe that we live in service of our descendants. We’re at a turning point in civilization. Those of us who are alive now have an especially crucial role to play. We must step up, don’t you think?

#1

#1  #1

#1  #1

#1  “Each beginning is the end of a waiting. We are each given exactly one chance to be. Each of us is both impossible and inevitable. Every replete tree was first a seed that waited.” –

“Each beginning is the end of a waiting. We are each given exactly one chance to be. Each of us is both impossible and inevitable. Every replete tree was first a seed that waited.” –  Lab Girl is for women in science and research, and women thinking of careers in science and research. But men in science and research will love the book, too.

Lab Girl is for women in science and research, and women thinking of careers in science and research. But men in science and research will love the book, too. By the way, Ann just released her new novel,

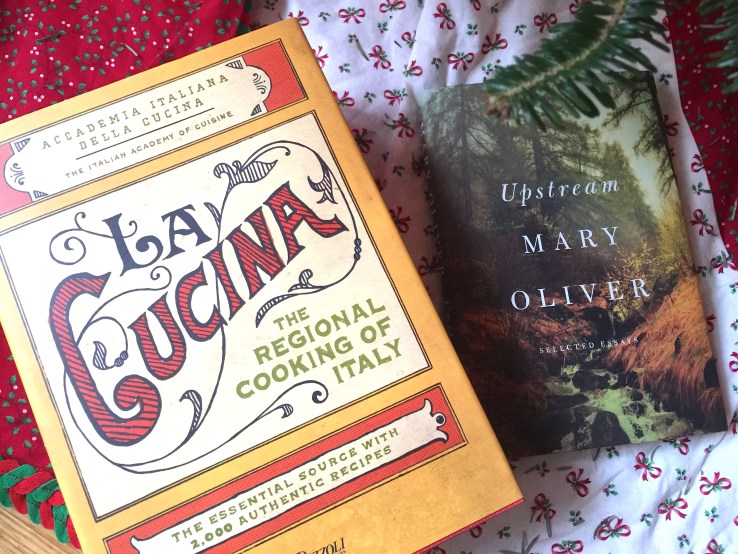

By the way, Ann just released her new novel,  Read a collection of essays:

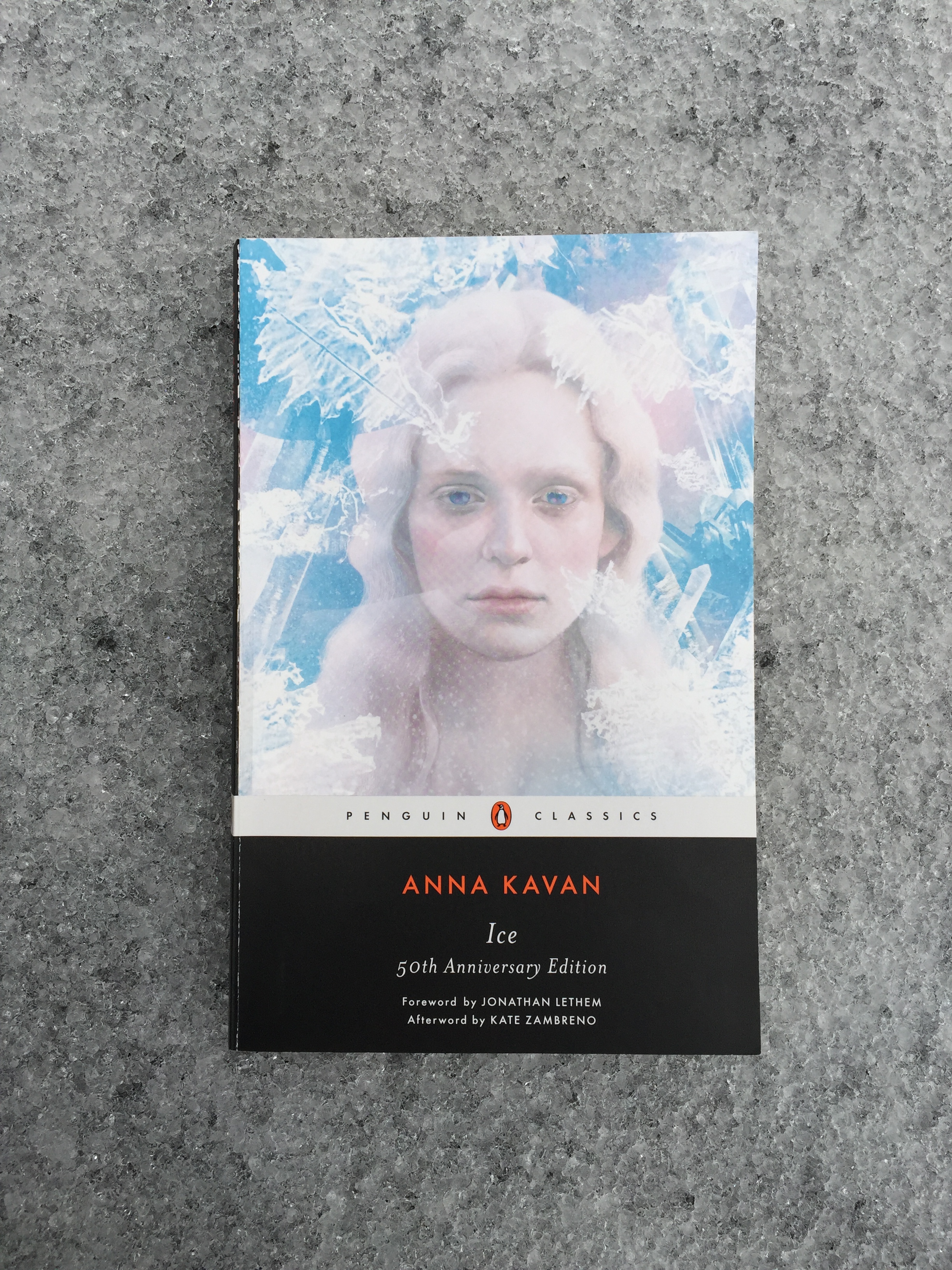

Read a collection of essays:  Read a dystopian or post-apocalyptic novel:

Read a dystopian or post-apocalyptic novel:  Read a book over 500 pages long:

Read a book over 500 pages long:  Read a book about politics, in your country or another (fiction or nonfiction):

Read a book about politics, in your country or another (fiction or nonfiction):

Further, I was impressed when I saw there was an introduction to her memoir by

Further, I was impressed when I saw there was an introduction to her memoir by  For further reading,

For further reading,