Two glorious, sun-filled November days in Utah’s Zion National Park stand out when I look back on the cross county trip we completed on Thanksgiving eve. Visiting late in the season turned out to be perfect – the weather was warm and the park wasn’t crowded with tourists.

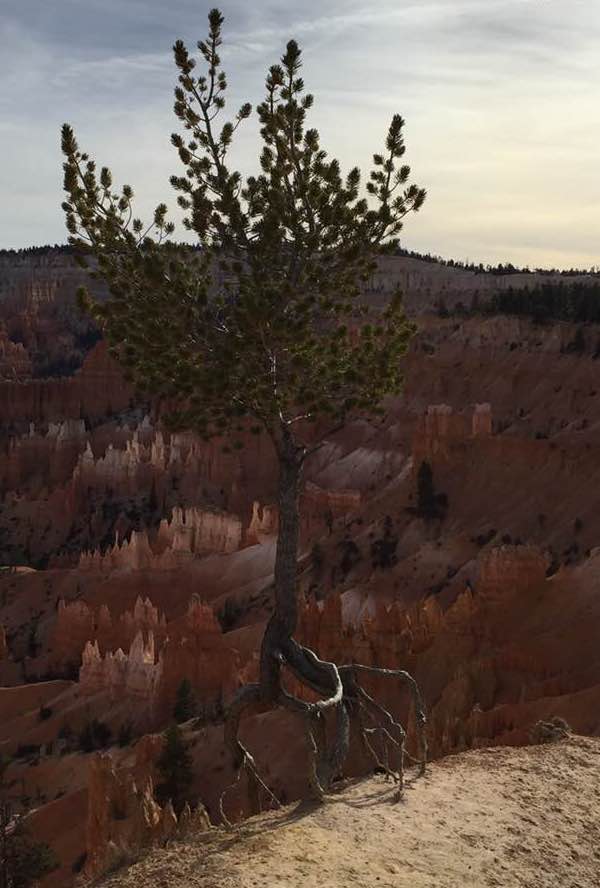

We went to four national parks in all: Zion, Carlsbad Caverns, the Grand Canyon, and Bryce Canyon. Zion was my favorite, while my husband’s was Bryce Canyon.

I found it frustrating that, while we took in some of our country’s most spectacular public lands, our current administration seemed to be dismantling the Environmental Protection Agency and has been intent upon shrinking our national monuments. People and corporations with great wealth, power and influence are determining the fate of our most beautiful and sacred lands.

In one of the national park bookstores, I bought Terry Tempest Williams’ The Hour of Land: A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks. It was published in 2016 to celebrate the 100th birthday of the National Park Service. Andrea Wulf, the author of The Invention of Nature, which I wrote about in a previous post, loves this book and so do I.

Terry Tempest Williams is one of our foremost nature writers and an important defender of the natural world. Years ago, I read her memoir, Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place and never forgot it. Williams was sitting on her pregnant mother’s lap one day in the 1950s when she actually witnessed the test explosion of a nuclear bomb in the Utah desert. Williams’ mother, grandmother, and six aunts subsequently died of cancer. Her book showed me the possibilities of memoir, and how the places we come from are inseparable from our personal histories.

I’m about half-way through The Hour of Land, which is partly a personal account of Williams’ love affair with selected national parks; partly a history of the founding of these protected places; and partly a lyrical tribute to nature and a call to stop pillaging the earth.

I’ve especially enjoyed her essays about Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming, “Keep promise,” and Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota, “All this is what the wind knows.” Williams writes of how the Rockefeller family for years enjoyed the unparalleled beauty of their Wyoming ranch, then secretly bought thousands more acres and donated it all for the creation of Grand Teton National Park.

She surmises that Teddy Roosevelt would be appalled that his namesake national park has been surrounded and encroached upon by drilling and fracking in the Bakken shale oil fields which span several states and part of Canada. The fields represent “the biggest rush of oil and gas in American history,” according to Williams. Her memoir addresses not only how we are treating the land, but how our insatiable desire to mine its resources can be inhumane and undermine communities.

Ironically, Williams’ father and two brothers have made their living in oil and gas. She writes:

“My brother Dan was one of these men who came to work in the Bakken in 2014 to make money. He worked during the winter on the frack line, washing off the chemicals used to break up the strata below so the oil can seep up to the surface more easily. The brutality of the weather only approximated the brutality of the work. Sixty degrees below zero in howling winds is man against nature; but week after week morphing into months of solitary darkness and freezing nights alone cramped in the cab of a truck is crazy making. Like so many of the workers profiled in Jesse Moss’s revelatory documentary about the Bakken oil fields, The Overnighters, one of the roughnecks hoping to turn his life around by the big boom said, ‘I arrived broken and left shattered.’ What began as a dream becomes a matter of survival, and for some, as in the case of my brother, just barely.”

Before our cross country trip, I know nothing of the Bakken oil fields. Traveling west, we enjoyed the exquisite beauty of places like Zion, but we couldn’t avoid scenes of a brutal existence when we passed through oil and gas fields similar to those at Bakken, with rows of storage containers to house workers, six or seven to a container. According to Williams, typically the worker shifts are twelve days on followed by twelve days off.

During our travels, we met a woman who lives near one of the communities upended by unfettered drilling and fracking. She spoke of the invasion of thousands of workers from all over the country looking for limited housing; exorbitant rents; and roughnecks who frightened the locals. One man she knew always carried a gun, even when he emptied the trash in his backyard.

Learning about all of this, I thought of two movies: Wind River, which came out this year, and the 2007 movie by Paul Thomas Anderson, There Will Be Blood .

But back to the beauty:

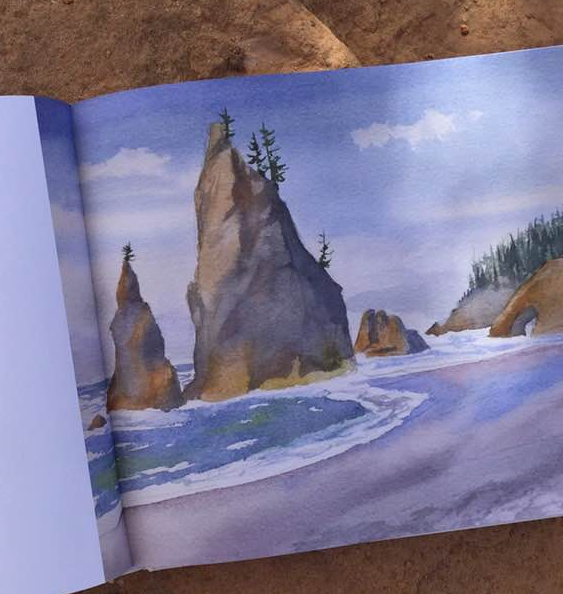

Last week I wrote about Molly Hashimoto’s book on watercolor painting, Colors of the West, and how each national park has its own palette. I especially liked Zion’s: the pink, russet, ochre and cream cliffs grab most of the attention, but I was also fascinated by the trees – piñon, juniper, fir, spruce, maple, ash, cottonwood and aspen – and how their surprisingly delicate fall colors contrasted with the red-hued rocks.

On two consecutive days, we hiked to Zion’s Emerald Pools and to Weeping Rock, where we encountered the most peaceful and stunning natural places I’ve ever seen. Water compressed between layers of sandstone seeps out and gives rise to gentle, sparkling waterfalls (depending on the season) and lush hanging gardens.

Take a moment to enjoy one of the Emerald Pools:

And Weeping Rock:

Coming up: Our cross country trip took an unexpected turn, and what was waiting for me at journey’s end.

The German scientist and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt has been largely forgotten, even though he was an international “rock star” of his time, and even though many parks, lakes, mountains, towns, and counties in the US are named after him. Andrea Wulf’s biography, published in 2015, has resurrected his legacy and spirit. Her book won the James Wright Award for Nature Writing, the Royal Geographical Society Ness Award, and many others, and it was named a best book of the year by many newspapers and publications.

The German scientist and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt has been largely forgotten, even though he was an international “rock star” of his time, and even though many parks, lakes, mountains, towns, and counties in the US are named after him. Andrea Wulf’s biography, published in 2015, has resurrected his legacy and spirit. Her book won the James Wright Award for Nature Writing, the Royal Geographical Society Ness Award, and many others, and it was named a best book of the year by many newspapers and publications.

On our road trip across the US (south to Florida, then west to Tucson, Arizona, then north to Portland, Oregon) we spent nearly two weeks visiting family in the St. Petersburg area. Along the way, we stopped in Savannah, Georgia, my first time in that lovely city. An afternoon wasn’t nearly long enough, but we did visit

On our road trip across the US (south to Florida, then west to Tucson, Arizona, then north to Portland, Oregon) we spent nearly two weeks visiting family in the St. Petersburg area. Along the way, we stopped in Savannah, Georgia, my first time in that lovely city. An afternoon wasn’t nearly long enough, but we did visit

with adorable Old Florida bungalows, many being renovated. Even though most of the windows of our airbnb were painted shut, we had air conditioning, and two large windows in the sleeping porch let in breezes from Tampa Bay two blocks away.

with adorable Old Florida bungalows, many being renovated. Even though most of the windows of our airbnb were painted shut, we had air conditioning, and two large windows in the sleeping porch let in breezes from Tampa Bay two blocks away.

“From 2000 to 2004, five Black young men I grew up with died, all violently, in seemingly unrelated deaths. The first was my brother, Joshua, in October 2000. The second was Ronald in December 2002. The third was C.J. in January 2004. The fourth was Demond in February 2004. The last was Roger in June 2004. That’s a brutal list, in its immediacy and its relentlessness, and it’s a list that silences people. It silenced me for a long time. To say this is difficult is understatement; telling this story is the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

“From 2000 to 2004, five Black young men I grew up with died, all violently, in seemingly unrelated deaths. The first was my brother, Joshua, in October 2000. The second was Ronald in December 2002. The third was C.J. in January 2004. The fourth was Demond in February 2004. The last was Roger in June 2004. That’s a brutal list, in its immediacy and its relentlessness, and it’s a list that silences people. It silenced me for a long time. To say this is difficult is understatement; telling this story is the hardest thing I’ve ever done.  If you enjoy memoir, Men We Reaped is a good one. If you want to sample the National Book Award short list for fiction, Ward’s novel, Sing, Unburied, Sing, would be a great choice. I hope to get to it soon.

If you enjoy memoir, Men We Reaped is a good one. If you want to sample the National Book Award short list for fiction, Ward’s novel, Sing, Unburied, Sing, would be a great choice. I hope to get to it soon.

“Martin holds his burning cigarette upright. The cherry is just barely visible in the dark; above it, the tower of ash. He turns it slowly, inspecting it from all angles. He says, ‘You want me to eat that scorpion?’

“Martin holds his burning cigarette upright. The cherry is just barely visible in the dark; above it, the tower of ash. He turns it slowly, inspecting it from all angles. He says, ‘You want me to eat that scorpion?’